sculpture in a series that tells the story

of the Métis on the Plains.

The installation includes three pieces,

with the focal point a large steel

sculpture of Sir John A. Macdonald.

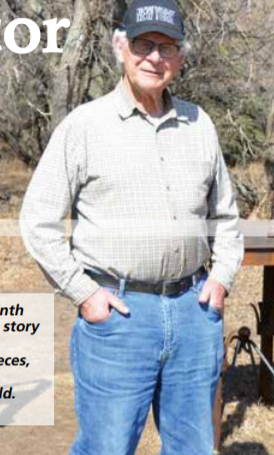

(Leader Photo by Tara de Ryk)

With his ninth sculpture in a series that reflects on the story of Métis life on the prairies complete, Girvin artist Don Wilkins is faced with a dilemma.

What to do with a sculpture of Sir John A. Macdonald? “We’re in a review of all historical figures now,” Wilkins said during an interview in his Girvin-area farmyard in early April. “I don’t know where it’s going to end.”

Behind him stands the towering metal sculpture of Canada’s first prime minister. It depicts Macdonald holding a rolled piece of metal that represents the British North America Act of 1867; the document that created the Dominion of Canada.

This was Macdonald’s great achievement and Wilkins, who finished the piece a year ago, admires him for it.

“Confederation didn’t happen overnight. It took a lot of work before hand,” Wilkins said. “Macdonald did a lot of work to convince Quebec to come along and form Canada.”

The intent when Wilkins began the project four years ago was that it would be placed along Highway 11, also known as Louis Riel Trail, becoming the ninth in a series of sculptures created by Wilkins that dot the highway from Chamberlain to Dundurn.

The sculptures represent a period of Plain’s history from 1850 to 1895 and are used as an interpretation of Métis life on the prairies. The series began in 1996 with a bison and Red River cart at Girvin.

More sculptures and Red River carts followed. They reflect Métis life and the changes as a result of European settlement and the extermination of the bison.

“By 1875, the buffalo were all but gone,” Wilkins said.

This greatly altered the Indigenous and Métis way of life. They had relied on the bison herds for their survival.

Wilkins said the highway is a place to showcase local art and history. Accompanying each sculpture is an interpretation explaining the idea behind the creation and its significance to the story Wilkins wishes to convey.

The Macdonald installation includes a small table with books on it and the sculpture.

All are fashioned out of steel welded by Wilkins. He’s thinking about adding a gothic arch as a backdrop to the three pieces, hoping it will augment the piece’s respectability.

“Hopefully, it will be an impetus that says this guy deserves some respect,” Wilkins said.

“I’m trying to work around Macdonald and the demonization of him.”

Wilkins laughingly points out that Macdonald, “Accomplished more drunk, than a lot of people do sober. He was brilliant.”

A founding father of Canada, Macdonald’s legacy as a nation builder has been heavily condemned in recent years, due to his government’s treatment of and policy of assimilation of Canada’s Indigenous people on the prairies.

Indigenous people of Saskatchewan suffered greatly in the late 1800s under various federal governments. Macdonald and his Conservative government enacted a series of policies in support of its national policy to unite Canada. This included building a railway across the prairies to the Pacific.

In recent years, many are rethinking honours to Macdonald. In 2018, the city council of Victoria, B.C., voted to remove a statue to Macdonald that stood on the steps of Victoria’s City Hall. Schools and awards named after Macdonald have been renamed.

In late March 2021, Regina city council voted to remove a Macdonald statue from Victoria Park. The decision was made after commissioning a report after controversy over the statue emerged in the summer of 2020.

The report concluded the statue should be removed because: “These policies include use of day schools and residential schools as tools of assimilation, relocation of Indigenous peoples away from traditional hunting and fishing areas to make room for European settlement, and an inadequate and often corrupt system for delivering rations to reserves.”

Regina council voted 7-4 in favour of removing and relocating the statue.

With his Macdonald sculpture complete, Wilkins waited a year for Regina city council’s decision.

Wilkins is aware of Macdonald’s legacy and says he didn’t create the sculpture without careful research into his subject.

When the controversy arose last summer, Wilkins did even more research, consulting various sources to learn about the different arguments.

The installation will include an interpretation of the piece that includes both positive and negative aspects of Macdonald’s legacy.

“I have a small library with books with different arguments,” he said. “When we look at his accomplishments, we are on land he worked with Great Britain to make sure we had a dominion from sea to sea.”

Wilkins said Macdonald was under great pressure to unite Canada.

“He didn’t want to procrastinate on Canada. He wanted Canada to be different than America, and he was at times fearful if he didn’t go to work on this, the Americans would come in and take over.”

Accompanying the sculpture is a plaque with an interpretation of the work. It reads:

“Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, clearly was a principal architect in the formation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867. An able parliamentarian, lawyer, and Conservative leader, he was determined to see our nation formed from coast to coast, including the Arctic.

“His accomplishments included the construction of an all-Canadian railway, completed by 1885. He initiated a system of protective tariffs in order that Canada’s fledgling industry could thrive. He formed a national, respected police force, the North West Mounted Police in 1874.

“His one great failure was to comprehensively understand the nature of the prairie North West, in particular First Nation and Métis people.

“The major consequence was the North West Rebellion of 1885. Upon the defeat of rebel forces, their leader, Louis Riel, was brought to trial and convicted of treason. Macdonald refused clemency and Riel was executed November 16, 1885.”

“I tried to be fair in my text and not give up my admiration for him,” Wilkins said.

This isn’t Wilkins’ first time dealing with an artistic interpretation of a controversial historical figure.

In 2015, Wilkins installed a sculpture of Riel at Bladworth. Viewed as a great leader and father of the Métis people, others see Riel as a traitor to his country. Called “The Invitation,” Wilkins chose to represent a moment in history when Riel was invited to return to Canada from the U.S. to lead the Métis.

It was a crucial time for the Métis, whose way of life was rapidly changing. First the bison were eradicated and then they were faced with losing their land because of the federal land survey. With “The Invitation,” Wilkins tried to represent Sculptor cont’d from page 10 a moment in time in 1884 when a peaceful resolution to the Métis question could be possible.

“If one expects leadership to be without fault, it’s an unrealistic expectation,” he said.

Coming back to the question of what to do with a sculpture of Sir John A. Macdonald, Wilkins, who turns 84 this year, is willing to complete the series and put the sculpture out there.

He needs to contact municipalities to find a location. As with his other installations, Wilkins handles the setup, site preparation and sometimes maintenance. He does this all at his own expense.

“I’m still thinking I’m going to place him. There is value to the story and take the risk,” Wilkins said. “When I do place him, it will be a topic of discussion. I’m not going to get away with it.” He expects debate.

Wilkins does not want people opposed to the sculpture to vandalize it. Instead, Wilkins says they should create their own art to get their message across.

“I tell people if you want to do that, then you build your own and place it. Don’t take somebody else’s effort and desecrate it.”

-Tara de Ryk

Leave a Reply